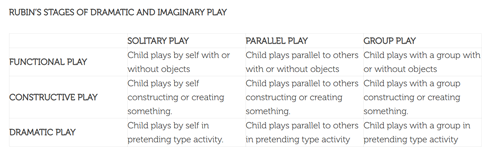

Rubin’s and his associate’s studies have done much to clarify the developmental levels of children’s play in light of our knowledge about children.

About

Kenneth H. Rubin (B.A., McGill University, 1968; Ph.D., Pennsylvania State University, 1971) is Professor of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology and Founding Director, Center for Children, Relationships, and Culture at the University of Maryland. Rubin’s research interests are focused on such topics as social, emotional, and personality development; social competence; social cognition; play; aggression; social withdrawal/behavioural inhibition/shyness; peer relationships and friendship; parenting and parent-child relationships; and cross-cultural studies.

Rubin and his associates have been working in understanding children’s social, dramatic and cognitive play. The research studies conducted in this area lead them to findings which were very similar to Mildred Parten and Sara Smilansky explanations about play.

The results obtained from Rubin’s and his associates studies clarifies of children’s play in accordance to their developmental milestone.

Characteristics Used To Define Play

They have also identified five characteristics that have been used to define play. These include (a) active engagement, (b) intrinsic motivation, (c) attention to means rather than ends, (d) nonliteral behaviour, and (e) freedom from external rules.

- Active Engagement - Children are active agents in their environments. They explore and figure out how to communicate and respond to events and people around them. Through the process of play, children engage in learning about the world by constructing knowledge through interaction with the people and the things around them (Chaille & Silvern, 1996). Children are active agents in their environment, for example, by being exposed to a variety of toys that will challenge their thinking skills and support the process of learning.

- Intrinsic Motivation - Intrinsic motivation is the inherent yearning for children to do something tangible because they will learn something new from their experience. Children are motivated to choose new playthings or activities because they offer a new challenge on a familiar experience. For example, LEGO bricks, the popular children’s toys, provide the opportunity to apply familiar constructive play skills in an innovative, comprehensive way. Children also use familiar objects or activities to offer a safe outlook on a new and perhaps discrepant experience (Monighan-Nourot, Scales, Van Hoorn, & Almy, 1987). For example, after seeing her mom prepare her lunch, Gabriela was seen playing in the playhouse, preparing herself a meal. Gabriela was performing a familiar activity based on her prior observation and experience.

- Attention to Means Rather Than Ends - While in play, children are less worried about a particular goal than they are about various methods of reaching it. Because the children themselves are establishing their own goals, the goals may change as play progresses. Once a child learns how to solve a puzzle, she or he might stack the pieces in new

arrangements or use them in a completely different activity. - Nonliteral Behaviour - Begins as early as the first year of life, is the distinctive feature of symbolic play (Fein, 1975). Children transform objects and situations to fit their play theme, such as pretending their fingers (their thumb and pinky) are a telephone. This concept of make-believe is thought to be a key factor in the hypothetical or “as if” types of reasoning called for in scientific problem solving. Make-believe may also play a part in the use of abstract symbols.

- Existence of Implicit Rules - Although there are no externally enforced rules in the types of play preschool children engage in, play often has implicit rules, maintaining the fantasy and reality distinction. An illustration is a group of children playing “doctor.” The behaviors of a girl playing the role of the doctor and a boy playing the patient with a scraped knee reveal the two children’s understanding of the rules pertaining to the roles of doctor and patient, as well as the children’s understanding of their relationship (Monighan-Nourot et al., 1987). Children are also capable of creating rules when entering a play situation. They develop a plan and presume their roles. This process of following rules and taking a role is an intrinsically motivated experience for children. Through this experience, children learn to understand their own roles and the rules that define them. Most important, children learn the roles and rules of others (Fein, 1984; Monighan, 1985). As a teacher, you can observe not only the play, but also the behind-the-scenes negotiations between the children that form the rules of their play. This observation will provide you with information of how children negotiate rules and understand the rules of their play.

Play Defined

Kenneth Rubin, Greta Fein, and Brian Vandenberg suggested that the following characteristics, when taken together, define play:

- Play is not governed by appetitive drives, compliance with social demands, or by inducements external to the behaviour itself; instead play is intrinsically motivated;

- Play is spontaneous, free from external sanctions, and its goals are self-imposed;

- Play asks "What can I do with this object or person?" as opposed to exploration tasks that focus on "What is this object (or person) and what I do with it (him or her)?";

- Play is not a serious rendition of an activity or a behaviour it resembles; instead it consists of activities that can be labelled as pre tense;

- Play is free from externally imposed rules and is thus different from games-with-rules (e.g., soccer, video games); and (

- Play involves active engagement.

Types of Play

During the first two years of life, play provides a window into the development of representational thinking.

In the first year of life, most play with objects is sensorimotor in structure and function. For example, babies tend to act on objects with little regard for their physical features (e.g., banging a plastic cup on the floor). By the end of the first year, infants become more discriminating and representational in their play. Objects are combined in "appropriate" and meaningful ways (e.g., an empty cup is brought to the mouth "as if" the child is drinking from it). These latter developments reveal critical components that reflect rapid growth in representational thinking. These components include: (a) decontextualized behaviour; (b) self-other relationships; (c) object substitutions; and (d) sequential combinations. Decontextualized behaviour involves the "out of context" production of familiar behaviour.

For example, by the middle of the second year, the toddler coordinates the use of several objects in his or her demonstrations of decontextualized behaviour (e.g., a 'Teddy Bear' is fed from an empty cup). This latter use of objects in pre tense captures the essence of the second developmental component of play, self-other relationships. When pre tense appears at about 12 months, it is centred around the child's own body (e.g., the child pretends to feed herself).

Beyond 20 months, and increasingly so up to about 30 months, the child gains the ability to "step out" of the play situation and to manipulate the "other" as if it were an active agent (e.g., a Teddy Bear "feeds" a doll with a plastic spoon). The developmental significance of these accomplishments should not be easily underestimated. Advances in maturity of play reflect the young child's increasing ability to symbolically represent things, actions, roles and relationships. A third component of play is the use of substitute objects. The ability to identify one object with another (e.g., a stick is used as a laser beam) is paradigmatic of symbolic representation. Finally, the fourth component of play is the coordination and sequencing of pre tense.

Between the ages of 12 and 20 months, toddlers' pretend acts become increasingly coordinated into meaningful sequences. At first, the child produces a single pretend gesture (drinking from a plastic cup); later, the child relates, in succession, the same act to the self and then to others (drinks from the cup, feeds the Teddy Bear from the cup). Subsequently, in a multi-scheme combination, the young child is able to coordinate different sequential acts (pours tea, feeds the Teddy Bear, puts bear to sleep).

By the preschool years and beyond, play can be classified along two dimensions: structure and social participation. The structural components refer to the types of activities in which individuals are engaged, such as simple functional activity, exploration and investigation of objects and environments, construction in which individuals build or create something, and imaginative dramatic pre tense. Social participation describes whether the activity is performed alone, in proximity to others, or in direct interaction with others. These two dimensions of play are orthogonal to one another, such that any structural activity can be performed alone, near others, or cooperatively with others. For instance, children might run around together on the playground, engaging in social functional play, or they might act out a pretend story with dolls by themselves, demonstrating solitary dramatic play.

Rubin’s Theories in Practice

- Do small group and large group activities

- Understand that children play together differently

- Social play changes depending on the child’s stage.

- Encourage children in imaginative play

- Provide opportunities for children to collaborate and negotiate with others.

- Children should be encouraged to take on different roles and perspectives during pretend play.

- Play should be informal, enjoyable and stress free.

References:

- Theories Of Play Part 5, Head Streams

- Rubin, University Of Michigan

- Play In Human Development, Research Gate

- Play and Learning Development, Sagepub

Toddlers have a greater understanding of the world around them by this stage. Their cognitive development (also known as intellectual development and thinking skills) continues

Toddlers have a greater understanding of the world around them by this stage. Their cognitive development (also known as intellectual development and thinking skills) continues Infants begin to develop trust when parents begin to fulfil their needs. Such as changing an infant's nappy when needed, feeding on request and holding

Infants begin to develop trust when parents begin to fulfil their needs. Such as changing an infant's nappy when needed, feeding on request and holding Beginning at birth the construction of thought processes, such as memory, problem solving, exploration of objects etc, is an important part of an infant’s cognitive

Beginning at birth the construction of thought processes, such as memory, problem solving, exploration of objects etc, is an important part of an infant’s cognitive Toddlers want to do more on their own and do not like it when you begin to establish limits on their behaviour. Tantrums can become

Toddlers want to do more on their own and do not like it when you begin to establish limits on their behaviour. Tantrums can become Your preschooler is now able to focus their attention more accurately and is less influenced by distractions. The intensity of questions increase as your child

Your preschooler is now able to focus their attention more accurately and is less influenced by distractions. The intensity of questions increase as your child John Dewey is often seen as the proponent of learning by doing – rather than learning by passively receiving. He believed that each child was active,

John Dewey is often seen as the proponent of learning by doing – rather than learning by passively receiving. He believed that each child was active, Toddler advance and gains new skills in Gross Motor Development milestones achieved throughout earlier years. Co-ordination and challenges that could not be performed before such

Toddler advance and gains new skills in Gross Motor Development milestones achieved throughout earlier years. Co-ordination and challenges that could not be performed before such Erik Erikson developed a psychosocial theory to understand how we each develop our identities through eight stages of psychosocial development from infancy to adulthood. The

Erik Erikson developed a psychosocial theory to understand how we each develop our identities through eight stages of psychosocial development from infancy to adulthood. The At this point preschoolers begin to interact effectively with others. Play becomes more innovative and organized and “boyfriend” or “girlfriend” begins to emerge. Preschoolers have

At this point preschoolers begin to interact effectively with others. Play becomes more innovative and organized and “boyfriend” or “girlfriend” begins to emerge. Preschoolers have From now, babies begin to identify and respond to their own feelings, understanding other's feelings & needs and interact positively with others. A baby's social and

From now, babies begin to identify and respond to their own feelings, understanding other's feelings & needs and interact positively with others. A baby's social and