Child-centered learning is the heartbeat of high-quality early learning services—it places the child’s voice, interests, and wellbeing at the core of every decision, interaction, and environment. Here's a comprehensive look at what it means and how it transforms practice.

What Is Child-Centered Learning?

Child-centered learning is an approach where:

- Children are active participants in their learning, not passive recipients.

- Educators observe, listen, and respond to children's cues, interests, and developmental needs.

- Curriculum emerges from children’s play, questions, and discoveries, rather than being pre-scripted.

It aligns with principles of the EYLF and supports outcomes like agency, identity, and wellbeing.

Core Principles

- Agency and Autonomy: Children make choices, express preferences, and influence their learning journey.

- Respect for Individuality: Each child’s culture, temperament, and developmental stage is honored.

- Play-Based Inquiry: Learning unfolds through exploration, experimentation, and imagination.

- Relationships First: Secure, responsive relationships are the foundation for learning.

How It Looks in Practice

| Element | Child-Centered Example |

|---|---|

| Environment | Flexible spaces with open-ended materials that invite exploration |

| Documentation | Learning stories that capture child voice, interests, and emotional cues |

| Curriculum Planning | Emergent plans based on observed play themes and child-led inquiries |

| Interactions | Educators scaffold learning by asking open-ended questions and co-playing |

| Transitions & Routines | Adapted to suit children's rhythms, preferences, and emotional needs |

| Family Partnerships | Families co-contribute to learning goals and share insights about their child |

Benefits for Children

- Builds confidence and self-worth

- Fosters critical thinking and creativity

- Supports emotional regulation and resilience

- Encourages collaboration and communication

- Strengthens cultural identity and belonging

Challenges & Considerations

- Requires deep educator reflection and flexibility

- Demands strong documentation skills to capture authentic learning

- Needs ongoing professional development in trauma-informed and inclusive practice

- Must balance child agency with safety and group wellbeing

Child-Centered Learning vs. Play-Based Learning

| Feature | Child-Centered Learning | Play-Based Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | The child as a whole person—their voice, agency, and wellbeing | The process of play as a vehicle for learning |

| Curriculum Driver | Child’s interests, needs, culture, and emotional cues | Play themes, exploration, and imagination |

| Educator Role | Co-learner, responsive observer, emotional guide | Facilitator of play, scaffold for inquiry |

| Learning Outcomes | Identity, agency, emotional safety, belonging | Creativity, problem-solving, collaboration, cognitive growth |

| Planning Approach | Emergent, relational, emotionally intelligent | Emergent, inquiry-based, often linked to developmental domains |

| Documentation Lens | Captures child voice, emotional states, and relational dynamics | Captures play narratives, learning dispositions, skill development |

| Environmental Design | Reflects child identity, sensory needs, cultural context | Rich in open-ended materials, invitations to play |

How They Intersect

- Play-based learning can be child-centered, but not all play-based programs prioritize child voice or emotional safety.

- Child-centered learning may include play but also embraces routines, rituals, and relationships as learning moments.

- Both value agency, but child-centered learning goes deeper into emotional intelligence, cultural responsiveness, and relational pedagogy.

Examples of Child-Centered Learning

1. Infant Cues and Responsive Routines

- An educator notices a baby turning away during a group song and gently adjusts the environment—lowering volume, offering a quiet cuddle space.

- Feeding and sleep times are adapted to each infant’s rhythm, not a fixed schedule.

2. Toddler Emotional Narratives

- A toddler repeatedly reenacts a “lost toy” scenario in dramatic play. The educator documents this and offers a storybook about loss and recovery, validating the child’s emotional processing.

- Transitions are softened with personalized rituals (e.g., a goodbye song or sensory object) based on each child’s comfort.

3. Preschooler Inquiry-Led Projects

- A group of children become fascinated by shadows. Educators co-research with them—exploring light sources, creating shadow puppets, and documenting their theories.

- Children vote on which materials to add to the outdoor space, and educators scaffold the decision-making process.

4. Cultural Identity and Belonging

- A child shares a family tradition during circle time. Educators invite the family to co-create a cultural celebration, embedding the child’s identity into the curriculum.

- Menus and documentation reflect children’s home languages and cultural symbols.

5. Child Voice in Documentation

- Instead of educator-only learning stories, children co-caption their photos: “I was building a trap for the monster!” or “I felt brave when I climbed.”

- Visual documentation includes emojis or emotion cards chosen by the child to express how they felt during the experience.

6. Trauma-Informed Adjustments

- A child flinches during loud noises. Educators introduce noise-canceling headphones and create a “quiet nook” with soft textures and calming visuals.

- Educators use visual schedules and social stories to support predictability and emotional safety.

Further Reading

Child Centred Approach

John Dewey's Theory

Child Initiated Learning

Guide To The Reggio Emilia Approach

How To Achieve Quality Area 1

Using Floorbooks With Children In Early Childhood

What Is Pedagogy In Early Childhood

Inquiry Based Learning In Early Childhood

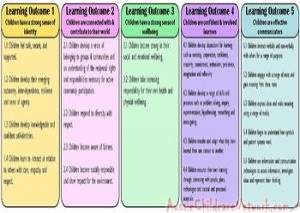

Here is the list of the EYLF Learning Outcomes that you can use as a guide or reference for your documentation and planning. The EYLF

Here is the list of the EYLF Learning Outcomes that you can use as a guide or reference for your documentation and planning. The EYLF The EYLF is a guide which consists of Principles, Practices and 5 main Learning Outcomes along with each of their sub outcomes, based on identity,

The EYLF is a guide which consists of Principles, Practices and 5 main Learning Outcomes along with each of their sub outcomes, based on identity, This is a guide on How to Write a Learning Story. It provides information on What Is A Learning Story, Writing A Learning Story, Sample

This is a guide on How to Write a Learning Story. It provides information on What Is A Learning Story, Writing A Learning Story, Sample One of the most important types of documentation methods that educators needs to be familiar with are “observations”. Observations are crucial for all early childhood

One of the most important types of documentation methods that educators needs to be familiar with are “observations”. Observations are crucial for all early childhood To support children achieve learning outcomes from the EYLF Framework, the following list gives educators examples of how to promote children's learning in each individual

To support children achieve learning outcomes from the EYLF Framework, the following list gives educators examples of how to promote children's learning in each individual Reflective practice is learning from everyday situations and issues and concerns that arise which form part of our daily routine while working in an early

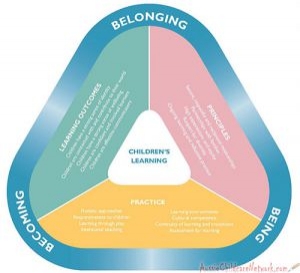

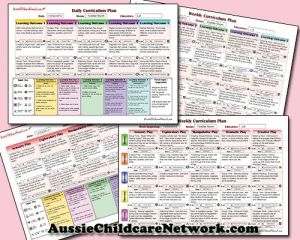

Reflective practice is learning from everyday situations and issues and concerns that arise which form part of our daily routine while working in an early Within Australia, Programming and Planning is reflected and supported by the Early Years Learning Framework. Educators within early childhood settings, use the EYLF to guide

Within Australia, Programming and Planning is reflected and supported by the Early Years Learning Framework. Educators within early childhood settings, use the EYLF to guide When observing children, it's important that we use a range of different observation methods from running records, learning stories to photographs and work samples. Using

When observing children, it's important that we use a range of different observation methods from running records, learning stories to photographs and work samples. Using This is a guide for educators on what to observe under each sub learning outcome from the EYLF Framework, when a child is engaged in

This is a guide for educators on what to observe under each sub learning outcome from the EYLF Framework, when a child is engaged in The Early Years Learning Framework describes the curriculum as “all the interactions, experiences, activities, routines and events, planned and unplanned, that occur in an environment

The Early Years Learning Framework describes the curriculum as “all the interactions, experiences, activities, routines and events, planned and unplanned, that occur in an environment