Experts on early childhood education have for some time believed that much more than the content of learning – like numeracy, literacy and science concepts – it is the acquiring of learning dispositions that ensure the best academic outcomes in the long run. The following article provides information on What Are Learning Dispositions, How Dispositions Change over Time and Context, Examples Of Learning Dispositions and more.

What Are Learning Dispositions

Learning dispositions can be understood as enduring habits of mind and actions that affect how students approach learning. The EYLF goes on to explain dispositions as “tendencies to respond in characteristic ways to situations, for example, maintaining an optimistic outlook, being willing to persevere, approaching new experiences with confidence.”

While education experts and childhood psychologists agree on the role that learning dispositions play in a child’s learning achievements, there is less unanimity on whether dispositions are inborn or learnt. Many people believe that children have natural ways of doing things and of being, perhaps as part of their biological makeup. But even though not all children may possess or apply these ‘habits of the mind’ as part of their normal manner of play and learning, it is important for educators to acknowledge that children have the capacity to develop positive dispositions. And this is why the EYLF includes learning dispositions in Learning Outcome 4 – Children are confident and involved learners. The idea of developing dispositions is suggested as becoming ‘more or less disposed’ to respond in a particular way rather than acquiring them.

How Are Learning Dispositions Important

Learning dispositions play a critical role in a child’s overall ability to learn and progress. Dispositions develop alongside and in conjunction with children’s acquisition of knowledge, skills, attitudes and understanding. For example, a group of children constructing with wooden blocks are developing the physical skills of grasping, placing and stacking as well as learning foundational numeracy about shape and size. However, these children are also developing a positive disposition of creativity, imagination, cooperation and enthusiasm as they plan, discuss and solve problems during their block play.

The other major significance of learning dispositions is that they help children learn to deal with failure. As the blocks come tumbling down or as another child runs by and collapses their tower, children will come face to face with the fact that despite best intentions, things might not always go as planned. By developing the dispositions of commitment, persistence and resilience, they will learn that people don’t always succeed the first time and that they may have to try again and again to achieve their objectives.

How Dispositions May Change Over Time

When considering how learning dispositions change over time, experts have pointed out the key role that educators’ actions play in strengthening or weakening them. Thus dispositions can be considered to progress when the following three dimensions grow stronger.

- Robustness – Children continue to learn even when conditions are not supportive, such as a toddler no longer needing to reassure themselves their mother is in sight to continue to be involved in an activity.

- Breadth – children realise that the habits that proved useful in one domain can be applied in another such as skills needed to complete a jigsaw puzzle being applied to creating a story.

- Richness – children become more flexible and sophisticated in persistence, questioning and collaboration. For example, Persistence might move from not giving up to later involving emotional maintenance or getting assistance.

How Dispositions May Change Across Contexts

A child may act differently in different situations because dispositions may become attached to activities and places. They may display confidence in conversations with an educator but not so in considering entering a play situation with peers. This is because relationships are crucial to developing and applying dispositions as they relate to a child’s feelings of belonging. Educators should therefore see that children feel secure about themselves and the people around them so that they are able to apply learning dispositions in a variety of situations.

Dispositions can also be positive or negative and this makes some dispositions less helpful than others for children’s learning and development. For example, a child who is never given the opportunity to dress themselves or to tidy up will tend to rely too much on an adult caregiver, thereby developing learned helplessness - a negative disposition. However, by encouraging the child to be responsible for their own belongings and by getting them to tidy up the play area or put things in the recycling bin, an educator can help them to develop positive dispositions of independence and self-reliance.

Examples Of Learning Dispositions

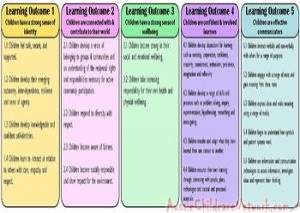

According to the EYLF Learning outcomes, element 4.1 states, “Children develop dispositions for learning such as curiosity, cooperation, confidence, creativity, commitment, enthusiasm, persistence, imagination and reflexivity”.

Learning dispositions most important for early childhood education and care thus include:

- Curiosity – this is the child’s natural state of inquisitiveness and desire to find out more. Curiosity helps children develop observation skills, think about things and figure them out.

- Cooperation – the ability to work with peers towards common goals and using common resources

- Confidence – the belief in one’s own abilities to learn and know.

- Creativity – the ability to able to express themselves and make meaning

- Commitment – the ability to keep doing what needs to be done regardless of one’s talents or moods

- Enthusiasm – the feeling of joyful motivation from within directed towards an experience, activity or task

- Persistence – continuing to do or to try to do something that is difficult.

- Imagination – the ability to mentally visualise or conjure up new and different possibilities, situations and scenarios

- Reflexivity - growing awareness of the ways that their experiences, interests and beliefs shape their understanding

How To Develop Positive Learning Dispositions In Children

You can help children develop positive learning dispositions by:

- modelling the disposition; for example, when going out with children on a nature walk, genuinely express a sense of wonder and joyful inquiry at how flowers bloom, caterpillars crawl or spiders weave their web. Yet another disposition that is important to model is resilience and coping with setbacks; for example, when plans are interrupted by bad weather, you can say, “We were planning to have a picnic today, but it’s much too wet. What do you think we could do instead? Maybe we could have our picnic inside today, and go to the park tomorrow?”. With older children, it might be more useful to use storytelling, role play, and puppetry sometimes to encourage and model certain dispositions.

- showing that you value the disposition by noticing and commenting on it. For example, when a child has spent a long time focusing on something or has finally managed to complete something you could say, “I saw you working hard on that- it looks great now!”

- providing opportunities for children to develop dispositions by allowing children enough time, space, equipment or encouragement to initiate, continue and extend play or experiences. Also, make sure they are not disturbed unnecessarily by other children or by adults; so you could remind a child, “Don’t disturb Sean and Lia just now, they are concentrating really hard on getting all those shapes into place” or extend play for another child by saying, “We will add a bit of time here so that you can finish making the construction before we head back inside”.

- taking individual differences and preferences into account, for example by introducing changes gradually, or by giving extra support to a child who needs it.

Strategies To Develop Learning Dispositions

According to the EYLF, Educators promote desirable learning dispositions when they:

- plan learning environments with appropriate levels of challenge where children are encouraged to explore, experiment and take appropriate risks in their learning. One of the ways you can do this is by providing learning environments that are flexible and open-ended; this can either be done intentionally, like keeping stones at certain places in the classroom to invite structured discussions about types of rocks and their features. Alternately, educators may be more of facilitators allowing children to choose their own activities like going on a nature walk where they are free to touch leaves, dig for worms, and turn over rocks.

- recognise mathematical understandings that children bring to learning and build on these in ways that are relevant to each child. This can be done by using their daily activities to ask questions about numbers or get them thinking of measurements, like, “How many places do you set for your family supper?”, “We need a glove for each hand – where is the other one?” or “ Which is the longer pencil – yours or mine?”.

- provide babies and toddlers with resources that offer challenge, intrigue and surprise, support their investigations and share their enjoyment. One of the ways of doing this is to make accessible storage, picture labels on shelving and boxes, low sinks for handwashing, low-level coat and apron racks, and space for personal items so as to build agency and independence in children as they go about choosing their own activities and practising routines.

- provide experiences that encourage children to investigate and solve problems. For example, arrange for a doll’s tea party and when children come upon challenges, encourage them to problem-solve for themselves by asking, “We don’t have enough cups for everyone, what shall we do?” or “How do well slice this pizza so that everyone gets an equal share?”

- encourage children to use language to describe and explain their ideas; sometimes this might require the educator to wait before offering support; allow the child time to think of the processes involved in a task, and if there is still a difficulty, ask the child, “Which part would you like help with?:

- provide opportunities for involvement in experiences that support the investigation of ideas, complex concepts and thinking, reasoning and hypothesizing; these can range from sink or swim activities to using a slide to find out which objects roll and which ones slide.

- encourage children to make their ideas and theories visible to others; provide access to varied stationery, art and craft materials so that children can represent their new understandings by colouring, drawing charts, cutting and pasting pictures or clay modelling.

- model mathematical and scientific language and language associated with the arts; for example, when working with children in the garden to plant seeds, say “Let’s observe seeds. How many days do you predict it will take for the seed to sprout?”

- join in children’s play and model reasoning, predicting and reflecting processes and language. For example, when they invite you to look at a ladybird on a leaf, you can say, “That’s an interesting bug you’ve found. I don’t know what it is. I haven’t seen one of those before. I wonder how we could find out more about it?”

- intentionally scaffold children’s understandings. For example, when exploring different objects and environments, talk about what you and the children see, feel, and do, for example, “Feel the bark on the cherry tree- it’s much smoother and shinier than the oak tree, isn’t it?”. Connect new knowledge to prior learning, for example, “What shape is this fruit? Where might we have seen something similar before” besides providing clues like, “Where could you look for something like that? Which friend might be able to help?”

- listen carefully to children’s attempts to hypothesise and expand on their thinking through conversation and questioning. So if you find some children talking about stamps, you might use questions like “How do you think letters can reach the right people across long distances” or “Why do people need to pay to send letters?” to create deeper engagement with the idea. Then children can be encouraged to investigate and look for answers with access to documentaries and books on stamps or surfing online. Build-in activities like getting children to measure the size of the stamps or sort them by colour.

- provide opportunities to apply dispositions like cooperation and collaboration. This can be done by having worked in pairs or small groups on tasks or projects; noticing and praising positive interactions or instances where children share resources or help each other out, for example, “You and Lana really worked well together to build the house. Would you like to sit together for a snack?”.

- allow children to use materials in different and innovative ways, or to combine different materials to build creativity and imagination.

Further Reading

EYLF Learning Outcome 4: Children Are Confident And Involved Learners - The following lists the sub outcomes, examples of evidence when children can achieve each sub outcome and how educators can promote and help children to achieve EYLF Learning Outcome 4: Children Are Confident And Involved Learners.

How Children Can Achieve EYLF Learning Outcomes - This is a guide for educators on what to observe under each sub-learning outcome from the EYLF Framework, when a child is engaged in play and learning.

Activity Ideas To Promote EYLF Outcome 4 - The following article provides activities to promote each of the sub-outcomes of EYLF Outcome 4 - Children Are Confident And Involved Learners.

References:

Learning To Learn, Zero To Three

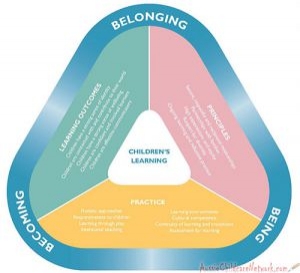

Belonging, Being and Becoming EYLF For Australia, ACECQA

Dispositions, Aistear Siolita, Practice Guide

Why Children's Dispositions Should Matter, Head Start, ECLKC

Here is the list of the EYLF Learning Outcomes that you can use as a guide or reference for your documentation and planning. The EYLF

Here is the list of the EYLF Learning Outcomes that you can use as a guide or reference for your documentation and planning. The EYLF The EYLF is a guide which consists of Principles, Practices and 5 main Learning Outcomes along with each of their sub outcomes, based on identity,

The EYLF is a guide which consists of Principles, Practices and 5 main Learning Outcomes along with each of their sub outcomes, based on identity, This is a guide on How to Write a Learning Story. It provides information on What Is A Learning Story, Writing A Learning Story, Sample

This is a guide on How to Write a Learning Story. It provides information on What Is A Learning Story, Writing A Learning Story, Sample One of the most important types of documentation methods that educators needs to be familiar with are “observations”. Observations are crucial for all early childhood

One of the most important types of documentation methods that educators needs to be familiar with are “observations”. Observations are crucial for all early childhood To support children achieve learning outcomes from the EYLF Framework, the following list gives educators examples of how to promote children's learning in each individual

To support children achieve learning outcomes from the EYLF Framework, the following list gives educators examples of how to promote children's learning in each individual Reflective practice is learning from everyday situations and issues and concerns that arise which form part of our daily routine while working in an early

Reflective practice is learning from everyday situations and issues and concerns that arise which form part of our daily routine while working in an early Within Australia, Programming and Planning is reflected and supported by the Early Years Learning Framework. Educators within early childhood settings, use the EYLF to guide

Within Australia, Programming and Planning is reflected and supported by the Early Years Learning Framework. Educators within early childhood settings, use the EYLF to guide When observing children, it's important that we use a range of different observation methods from running records, learning stories to photographs and work samples. Using

When observing children, it's important that we use a range of different observation methods from running records, learning stories to photographs and work samples. Using This is a guide for educators on what to observe under each sub learning outcome from the EYLF Framework, when a child is engaged in

This is a guide for educators on what to observe under each sub learning outcome from the EYLF Framework, when a child is engaged in The Early Years Learning Framework describes the curriculum as “all the interactions, experiences, activities, routines and events, planned and unplanned, that occur in an environment

The Early Years Learning Framework describes the curriculum as “all the interactions, experiences, activities, routines and events, planned and unplanned, that occur in an environment